IN-PREP HANDBOOK

Policy or decision-maker

You are a decision maker interested in enhancing inter-organisational disaster response collaboration?

You might want to learn more about the following topics:

General Suggestions

Initial suggestions based on lessons learned in TTXs, FSXs,

IN-PREP workshops and end-user interviews:

“Interoperability is not about relinquishing power but enhancing cooperation.”

Overall, a step-wise approach should be taken to enhance collaboration:

- Assessing the Status Quo

- Develop a legal basis/ a governance framework

- Specify collaboration:

- Information sharing and related baseline procedures are essential

- Then joint planning needs to take place.

- Finally, training and exercise on the developed plans are needed. Ideally, joint training programmes are developed (which may also create cross-organisational efficiency gains).

Assessment/ Evaluation and feedback mechanisms should be established with a “Plan-Do-Check-Act” cycle in which the evaluation results are addressed.

Ideally, central funding should be made available

Lessons learnt about collaboration should be centrally collected and also shared with others (e.g. at EU level)

“Build the actions on evidence”

To enhance the Status Quo, several interview partners suggested starting with an assessment of the Status Quo. These assessments can come in different forms:

- A map specifying the range of bilateral agreements that may exist at the regional and local level

- A review of past events to analyse the strengths and weaknesses in inter-organisational collaboration

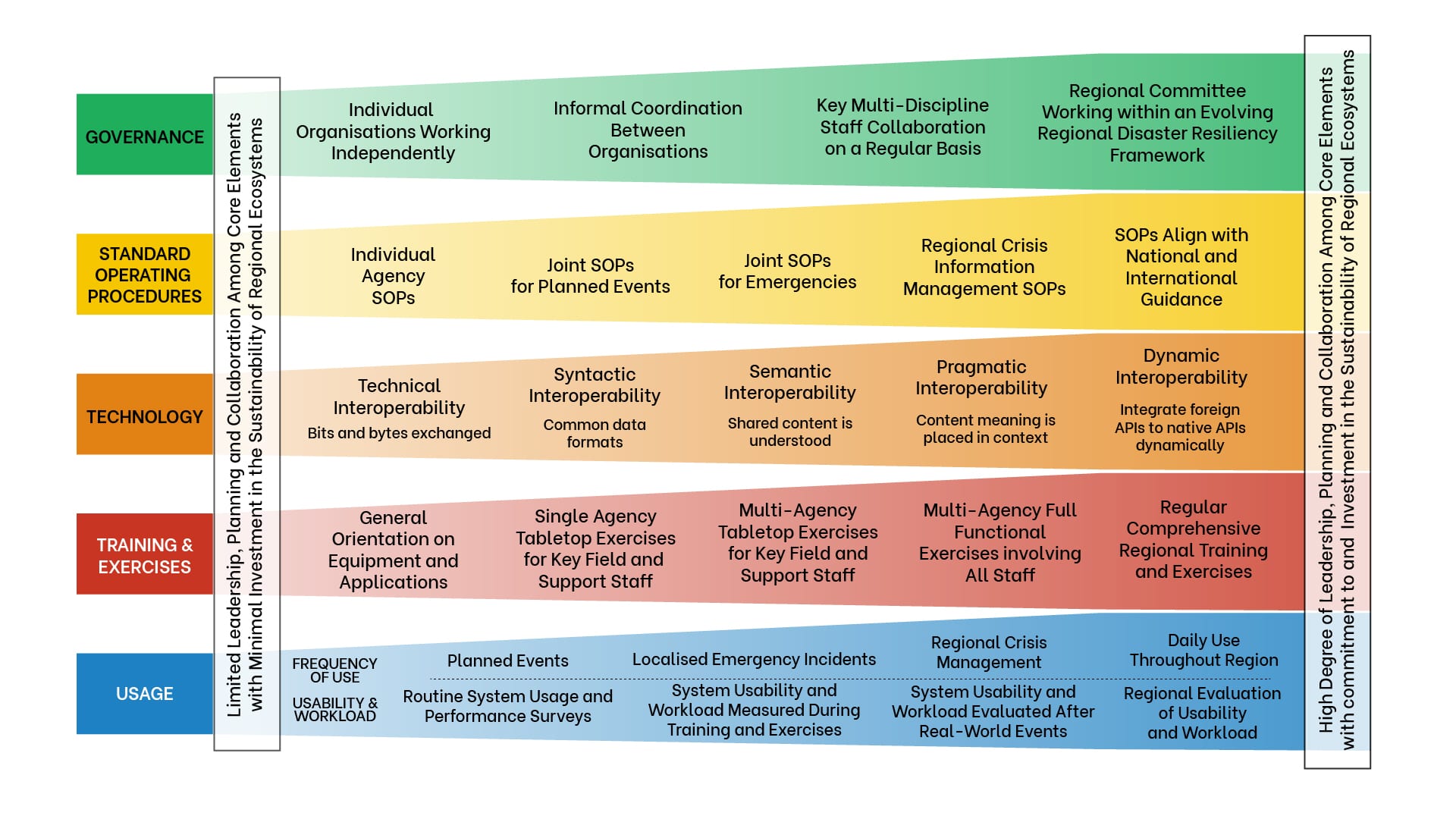

- A self-assessment based on the Interoperability Continuum to specify areas for future action.

The IN-PREP Interoperability Questionnaire can be found HERE

“A governance framework ensures that collaboration does not only depend on personal relationships.”

Develop a legal basis

As a next step, framework conditions for collaboration have to be set. In many cases, a legal basis has been created to facilitate collaboration. For example, the Netherlands have started the creation of their Safety Regions after the fireworks disaster in Enschede in May 2000 and the New Year’s fire in the ‘De Hemel’ bar in Volendam in 2001. These Safety Regions function as collaborative entities between several civil protection actors such as fire services, medical assistance and crisis management under one regional management board. The development of the Safety Regions furthermore acknowledged the increasing complexity of society together with emerging “forms of threats [including terrorism which] require a different type of approach, different partners and a different strategy.”[1] Similarly, in the UK, the Civil Contingencies Act 2004[2] provides a single framework for civil protection and seeks to reinforce partnership working at all levels.

Co-design Emergency Plans and (Standard) Operating Procedures

In a second step, plans and operating procedures can be created jointly by the relevant organisations. Several examples as to how this has been approached by certain sectors or countries but also on a multi-national basis are sketched in this handbook. Particularly for sectoral collaboration, it can save a lot of time and effort to build on existing SOPs. Capacities and functionalities could be described at a more abstract level in plain language to be understandable by all organisations. If needed, these can be specified by the individual organisations into their terminology.

It is important that a shared goal is to develop although institutional agendas may vary. The protection of lives should be the guiding principle in multi-agency settings.

The developed plans and SOPs should be linked with (national) risk assessments.

Training and exercising (joint) procedures are obviously an essential part of enhancing collaboration. To ensure that training and exercises are implemented regularly, a respective legal basis and related funding would be beneficial. Overall, “hard” and “soft” issues (technical/human) aspects have to be addressed.

The development of joint training courses helps to integrate collaboration deeply. In addition, it may help to save resources. Respective training may even be mandatory when wanting to move to the next career step.

Due to a frequent turnover in staff, training and exercises have to be implemented on a very regular basis, ideally every 9-18 months.

Involvement of actors:

- Ensure that all actors relevant for the scenario under consideration are involved in the exercise and particularly also its preparation. This holds also true for private actors such as (critical) infrastructure operators, the military etc.

- Early on, share your yearly exercise planning with partner organizations / private actors and give them the option to join in on certain exercises. This improves the possibility that they are able to get involved early in the exercise planning process.

In terms of individuals, ideally, they meet physically and get to know each other at the forefront to establish trust

Defining (joint) exercise goal and sub-goals:

Training goals need to be clearly defined. For example, the focus may be on the execution of whole plans or SOPs or the phase between the event and the creation of command lines, i.e. about the first 30 minutes of an event only. The latter obviously allows for more repetitions and scenario variations. The general approach then allows the identification of actors and scenarios etc.

Language:

- Identify a language that is shared by all participants; in the mid-term, respective language courses may have to be made mandatory for key actors

- Try to define a shared terminology.

- Partners should avoid using technical jargon and abbreviations. Wording for capacities / functionalities should relate on a more abstract level to what is needed and the respective liaison officers should translate into their internal wording.

- Build on established glossaries and initiatives to standardise communication.

Use of data:

Which data should be included in the exercise and can be shared with others? Also, invest in the trustworthiness of the data, and define clearly who is the owner/provider of the data to improve trustworthiness from the other involved actors.

The digital sharing of plans allows for a comparison of plans between organisations and even across local geographic boundaries. Ideally, reporting structures are similar to allow for better comparison. This again could be requested by respective legal requirements. Also, the sharing of lessons learned via a portal may be useful to keep track of learnings and re-integrate them into the governance framework and plans.

Relevance

Why is cross-organisational collaboration relevant for policy makers?

In all major incidents, organisations need to collaborate at different scales, including local, regional, national or even international level. However, collaboration between different actors can be difficult, depending on the level of interoperability they have reached. At the lower levels, Standard Operating Procedures are frequently developed at an organisational level, technologies are purchased individually and also trainings often relate to single organisations only. Hence, procedures and technologies do not necessarily match cross-organisational, if interoperability is low.

The level of interoperability is also guided by a range of ethical and privacy concerns. Indeed, organisations and regions follow different privacy and ethical guidelines, legislation, and cultural expectations. Bringing these together can be a challenge and, if not done carefully, can also lead to distrust.

In smaller incidents, respective challenges do not attract much attention. In major incidents however, they become visible. Some examples encompass:

- London Terrorist Attacks 2005:

The Pollock Report (2013), reviewing past UK incidents states that “The evidence demonstrates, therefore, a need for a review of the extent and scope of inter-agency training. Such training is vital in helping to reduce confusion and in fostering a better understanding of the emergency services’ respective roles”. - The Netherlands, creation of Safety Regions:

After several events between 2000 and 2003, the Dutch Safety Regions Act was developed in the Netherlands:

“The Dutch Safety Regions Act has a long history that includes some very tangible events that have led to its adoption, such as the fireworks disaster in Enschede in May 2000 and the New Year’s fire in the ‘De Hemel’ bar in Volendam in 2001. […] Because the threat from ‘classic’ disasters was broadened to include different types of disaster – like the foot and mouth crisis of 2003, the threat of a flu epidemic, the threat of terrorism and the ‘gritting salt crisis’ – disaster management has also been expanded over the years to include crisis management. The new forms of threat require a different type of approach, different partners and a different strategy.” (p. 5) - The Manchester Terrorist Attacks 2017:

At just after 22:30hrs on Monday 22nd May 2017, a suicide bomber detonated an improvised device in an area known as the City Room. Around 14,000 people, mainly teenagers and family, had travelled from across the UK to attend the concert. The bomb killed twenty-two people including many children. Over one hundred were physically injured and many more suffered psychological and emotional trauma. The Kerslake Report reviewed the related preparedness and response activities. While many things went well, several learnings could be identified. For example, the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service (GMFRS) did not arrive at the scene and therefore played no meaningful role in the response for almost two hours (p. 8) and stayed “effectively ‘outside the loop’, having no presence at the rendezvous point established by the Police, little awareness of what was happening at the Arena”. - The Germanwings Crash 2015:

After the Germanwings crash, international media assumed that French standards for privacy were standard across Europe and they reported on the German co-pilot’s name and information about his private life. However, cultural privacy practices in Germany had meant that until the reporting in the international media, not even the pilot’s name had been released within German Media (Falola and Birnbaum, 2015). Revealing the name upset those involved in the investigations as well as the public managing the trauma. -

Ramstein Air Base Accident 1988:

A flight manoeuvre that went wrong led to an accident in Ramstein on the US-Air Base with 70 dead and about 1000 injured. There were problems in the coordination between the American and German helpers, especially in care of the injured due to the differences in the systems: the American armed forces, which use a load-and-go system, and the German relief forces, which were seeking a local sighting and care. Thus, some of the injured ‘disappeared’ and then reappeared unannounced in hospitals with an American transport. There was no chief emergency physician on the premises and thus no structured emergency disaster medicine, which led to serious consequences. The communication failed completely, some helpers weren’t even allowed to go in the air base area. (Source; as well as rettungsdienst.de) -

Mont Blanc Tunnel Fire 1999:

As one side of the Tunnel was managed by Italians and the other by French, there was no communication between the different brigades. The alarm of the Italians reached the French with a delay. Nobody really knew about what the other side was doing and how many vehicles were actually affected and how many people were hidden in the security rooms, thus causing the death of many people. (Source)

Dimensions

What does cross-organisational collaboration encompass at the national and international level?

Cross-organisational collaboration or aspects of interoperability can be assessed and enhanced among several core domains. In the civil protection context, first steps have been made in the United States by developing an Interoperability Continuum. It was a result of the 9/11 attacks (Source PDF , p. 44, accessed 04.05.2020)

Thomas, J. & A. Squirini (n.a.): Measuring Systems Interoperability: A Focal Point for Standardized Assessment of Regional Disaster Resilience, p. 3, available via: Source PDF (9.11.2020).

Multiple European states have adapted this approach of differentiating dimensions of interoperability such as Governance, Standard Operating Procedures, Technology, Training and Exercises and Usage. For example, the UK in 2009 (Source PDF), Belgium (Testelmans 2017), and France (Mannaioni et al. 2020) built on this approach.

Interoperability Questionnaire

*Please note that while this works in the Chrome browser, other browsers can have issues displaying interactive PDFs correctly. If you run into any issues, please download and complete it using Adobe Reader.

The Interoperability Matrix has been adapted into an interactive questionnaire so that users can gain a better understanding of how they are currently faring from an interoperability perspective and where they can use the Handbook to improve. It is suggested that you conduct the assessment jointly with representatives of (potential) partner organisations. The interoperability of an organisation can only be assessed relative to other organisations.

TransCrisis Survey

The TransCrisis survey helps to analyse whether, and to which extent, a particular organisation or policy sector is ready to face a transboundary crisis. It should be noted that this is not an IN-PREP product but an external link to a tool created by a partner project.

Some ethical challenges at the governance level:

For each of these points illustrated in the image above (governance, standard operating procedures, technology, training and exercises, usage) there are diverse privacy and ethical implications that may affect collaboration and aspects of interoperability. It is well acknowledged among disaster practitioners that what risk means is not the same on two sides of a border. Thus what technology, practices, training, and data is needed to assess risk can greatly differ (Abad et al., 2018). What ethical concerns – including cultural priorities are evoked by a crisis are not universally normative but culturally grounded and thus not likely to be resolved through consensus (Leonelli, 2016; Fiore-Gartland and Neff, 2015).

It is important to not treat interoperability as an organisational problem with a technological solution: where if there is the will and the technology supports data exchange, then organisational and personal cooperation and collaboration will follow. Studies have suggested that focusing on interoperability as a primarily technological issue will not solve the organisational and cultural challenges that affect disaster response organisations, such as lack of resources, incommensurable working methods and terminologies, or resistance to change (Allen, Karanasios, and Norman 2013).

To encourage cooperation, therefore, it is recommended that a memorandum of understanding be established prior to use where important definitions, parameters, and guidance pertaining to privacy and ethical principles are established. These should support organisations in readily seeing their values and normal practices in the collaborative efforts, so none feel as though they have to cede authority or ownership.

Abad, J., Booth, L., Marx, S., Ettinger, S. & Gérard, F. (2018). Comparison of national strategies in France, Germany and Switzerland for DRR and cross-border crisis management. Procedia engineering, 212, 879-886.

Leonelli S. (2016). Locating ethics in data science: responsibility and accountability in global and distributed knowledge production systems. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 374, 1-12. Source

Allen, D. K., Karanasios, S., & Norman, A. (2013). Information sharing and interoperability: the case of major incident management. European Journal of Information Systems. http://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2013.8

EXAMPLES

Strong legal basis defining binding requirements for collaboration

United Kingdom

In the UK, The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 provides a single framework for civil protection and seeks to reinforce partnership working at all levels.

The Civil Contigencies Act built the basis for the Development of a Joint Doctrine for the emergency services (JESIP):

The key components of the Joint Doctrine are:

Principles for Joint Working – the principles we expect commanders to follow when planning a joint incident response

M/ETHANE – a common method for passing incident information between services and their control rooms

Joint Decision Model (JDM) – A common model used nationally to enable commanders to make effective decisions together

Based on the Contigencies Act and the associated Contingency Planning Regulations 2005 and guidance , the National Resilience Capabilities Programme (NRCP) and Emergency Response and Recovery , the UK: Local resilience forums were developed. Local resilience forums (LRFs) are multi-agency partnerships made up of representatives from local public services, including the emergency services, local authorities, the NHS, the Environment Agency and others.

IRELAND

In Ireland, The Framework for Major Emergency Management was developed in 2005 and was adopted by Government decision in 2006.

The document replaces the Framework for Co-ordinated Response to Major Emergency, which has underpinned major emergency preparedness and response capability since 1984. The

new Framework was prepared under the aegis of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Major Emergencies, and has been approved by Government decision. The National Steering Group for the implementation of the Framework was established

by Government Decision and replaces the Inter-Departmental Committee on Major

Emergencies.

One of the key objectives of the Framework is to set out the arrangements and facilities for effective co-ordination of the individual response efforts of the Principal Response Agencies to major emergencies, so that the combined result is greater than the sum of the individual efforts. The Framework assigns responsibility for undertaking the co-ordination function clearly and unambiguously and requires it to be supported so that it happens and is effective:

For details about the steering group, have a look at Appendix F2: Source PDF

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the Dutch Safety Regions Act was introduced in 2010.

In short, the effectiveness and professionalism of the emergency services in the Netherlands had to be increased. In order to bring this about, uniform service levels had to be established within cooperation areas (security regions) to facilitate mutual assistance and escalation.

The Safety Regions Act seeks to achieve an efficient and high-quality organisation of the fire services, medical assistance and crisis management under one regional management board. The Act stipulates that as a common rule, safety regions must be structured on the same scale as the police regions. The Safety Regions Act lays the foundations for organising disaster and crisis management with the aim of better protecting citizens against risks.

This legislation is furthermore facilitated by a joint Situation Assessment, called LCMS (Dutch Nation Wide Crisis Management System). LCMS is a nation-wide crisis management system used in The Netherlands to maintain and share a common operational picture supporting large-scale crisis management collaboration.

LCMS is used by all 25 safety regions, the majority of the waterboards, Rijkswaterstaat, an increasing number of emergency health care organisations, the Royal Military Police organisation and some drinking water providers. LCMS supports netcentric collaboration, which is a way of working in which clear agreements are made about sharing information so that decision-making under (crisis) circumstances is always based on an up-to-date, consistent and common operational picture. LCMS is a web based collaboration environment with a very high level of availability. The environment can be used to share information within an organisation as well as between organisations. It supports maintaining and sharing geographical as well as textual pictures.

PORTUGAL

In Portugal, the Integrated System for Relief and Protection Operations (SIOPS) is operated.

SIOPS is a set of rules and procedures, which guarantee that civil protection agents act, at the operational level, in a coordinated way and under a unique command. SIOPS is facilitated by inter-organisational command centres: the National Coordination Centre (CCON) district coordination centres using a joint software for situation assessment.

https://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/civil_protection/vademecum/pt/2-pt-1.html

http://www.prociv.pt/pt-pt/PROTECAOCIVIL/SISTEMAPROTECAOCIVIL/SIOPS/Paginas/default.aspx

Soft legal basis combined with individual/organisational engagement

The UNITED STATES

In the United States after the 9/11 attacks, the Interoperability Continuum was designed to help the public safety community and local, tribal, state, and federal policymakers address critical elements for success as they plan and implement interoperability solutions.

BELGIUM

In Belgium, the 2016 terrorist attacks marked an important trigger for addressing interoperability aspects in civil protection.

A single Incident Command Systems was introduced in 2017 “ICMS has been implemented in Belgium as the nation-wide emergency management system, in just 9 months, in 4 languages, with 4000 connected organisations” (http://icmsbelgium.net/). A joint curriculum on emergency planning was developed at a national level.

TRAINING

United Kingdom

Under the JESIP Framework for cross-organizational response, trainings have been developed.

They encompass for example, all staff training, commander training, control room training or operational communications adviser.

https://www.jesip.org.uk/all-staff-training

https://www.jesip.org.uk/commander-training

https://www.jesip.org.uk/control-room-training

https://www.jesip.org.uk/operational-communications-adviser

The trainings are accompanied by documents such as the “Consolidated Command Trainer Guide”

https://www.jesip.org.uk/uploads/media/pdf/Jesip-Awareness/Consolidated_Command_Trainer_Gui.pdf

Exercises

IRELAND

In Ireland, under the Framework for Major Emergency Management, a guide to planning and staging exercises was developed in 2016.

It differentiates different types of exercises (table top and live) and the different steps to be considered in the planning and implementation process:

http://mem.ie/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/A-Guide-to-Planning-and-Staging-Exercises.pdf

United Kingdom

In the context of the JESIP Joint Doctrine, guidance has been developed for multi-agency exercises in the UK:

https://www.jesip.org.uk/testing-and-exercising

An Exercise Assurance Framework has been produced to help with the planning of a one-day multi-agency live play exercise allowing multiple staff to take part. Other templates which may be useful include:

Agreements and protocols with neighbouring countries

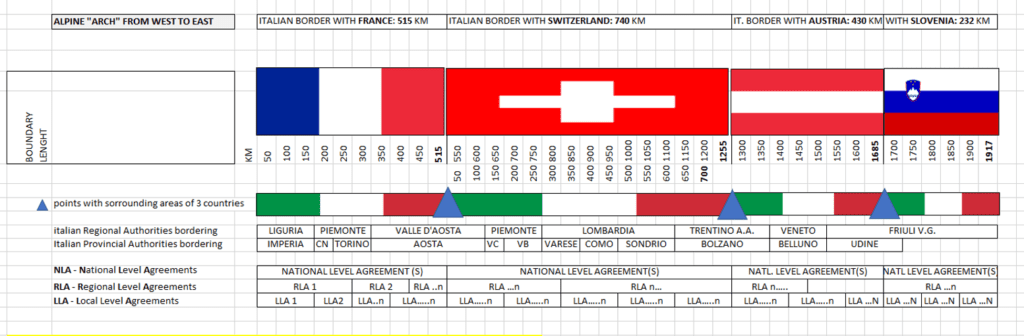

In border regions, agreements and protocols are frequently in place since support might be activated faster than national support. Also, in case that a state cannot deal with an incident on it‘s own, neighbouring states might provide support and in some areas, strategic collaboration is place. Some examples and ideas to get an overview of the own situation are indicated below:

Please bear in mind that while some states have no or only one neighbouring state, certain countries have several neighbouring countries.

Deriving an overview

One example for deriving an overview of protocols and agreements for countries with several neighbouring countries in which also regional and provincial authorities play a role, is the below example of Italy. It relates the border line with neighbouring countries to the local authorities and specifies the protocols in place.

In addition, it could be useful to conduct joint risk assessments with the neighbouring countries or exchange information about the own assessment with relevance for the neighbouring state. If needed, additional agreements could be based on these assessments. Joint exercises might also serve as a basis to identify needs for protocols and to test existing ones.

Ethics

Collaborators need to articulate stewardship and care protocols in addition to the MOUs around each organisation’s roles and responsibilities. These should include details about the interactions they prioritise to support planning for response, recovery, and resiliency.

These protocols should be detailed enough to support those establishing trainings to appropriately customise their efforts for specific collaboration situations. Existing organisational ethical frameworks around these two issues could be used as a starting point.

Collaborating Agencies need to be proactive in how they address diversity. This can be through Diversity and Gender Equality Plans for their training and SOP processes. Following the humanitarian “good enough needs assessment” in tool design can also support this (ACAPS and EPB, 2014).

Building solidarity and trust through these activities also requires collaborating organisations to develop what are termed ‘articulation mechanisms’ (Doherty, 2012). These are methods by which actors are able to be aware of others, express difference, and align activities. This should include specification of shared meaning standards that need to be in place prior to any collaborative effort so a responder from Agency A to confirm their understanding of what was just input by Agency B and methods for them to highlight potential mismatches in meaning.

The Assessment Capacities Project and Emergency Capacity Building Project (ACAPS and EPB). (2014). Humanitarian Needs Assessment, The Good Enough Guide. UK: Practical Action Publishing. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/h-humanitarian-needs-assessment-the-good-enough-guide.pdf

Doherty, G., Karamanis, N., & Luz, S. (2012). Collaboration in translation: The impact of increased reach on cross-organisational work. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 21(6), 525-554.

EXAMPLES

The Euregion Meuse-Rhine Incident control and Crisis management (EMRIC) is a unique collaboration of public services, that are responsible for public safety, including fire services, technical assistance and emergency medical care in their respective territories.

In a region that is so rich of borders, like the Euregion Meuse-Rhine, emergency services from abroad can often be at the scene of the incident faster than own services. When every second counts, fast assistance is vital.

The collaborating servcies are the fire services of Aachen, the Ordnungsamt from Kreis Heinsberg and the Ordnungsamt from the Städteregion Aachen in Germany, de Province of Limburg and Liège in Belgium and the Veiligheidsregio and GGD Zuid-Limburg in the Netherlands. These are the organisations that fund the collaboration and the so-called EMRIC office. In addition to these seven partners, over 30 services and governments are involved in the EMRIC collaboration.

EMRIC ensures that cross-border collaboration is possible, however, self-evident it is in the least. Within these three countries, operational and legal systems differ to such extent, that a lot needs to be arranged, before ambulance or fire trucks are allowed to cross the border. In a region that is so rich of borders, like the Euregion Meuse-Rhine, working, recreating and studying across the border has become self-evident, however, this was not the case for assisting each other in case of emergencies.

https://www.emric.info/en/citizens/what-is-emric?set_language=en

Joint ethical framework examples

More resources to support establishing agreements can be found at: www.itisethical.eu

Sending and receiving UCPM support

In case you want to enhance capacity to send or receive international support, you might be interested in the following sub-topics:

Sending support (UCPM)

The overall objective of the EU Civil Protection Mechanism is to strengthen cooperation between the EU Member States and 6 Participating States in the field of civil protection, with a view to improve prevention, preparedness and response to disasters. When the scale of an emergency overwhelms the response capabilities of a country, it can request assistance via the Mechanism.

UCPM trained experts

The EU Civil Protection Mechanism runs an active and comprehensive training programme, offering experts from all over Europe a deeper knowledge of the requirements of European civil protection missions.

The training helps experts improve their coordination and assessment skills in disaster response.

The programme offers a wide range of courses from basic training to high-level sessions for future mission leaders. Special courses are also available aiming to prepare for specific aspects of missions such as security training or assessments.

In addition, the expert exchange system of the EU Civil Protection Mechanism allows for the secondment of civil protection experts from one EU Member State or Participating State to another. This exchange provides participants with knowledge and experience on all aspects of emergency intervention and the different approaches of national systems.

https://ec.europa.eu/echo/what/civil-protection/experts-training-and-exchange_en

EU Civil Protection Pool

The European Civil Protection Pool was established to advance European cooperation in civil protection and enable a faster, better-coordinated and more effective European response to man-made disasters and natural hazards.

The Pool brings together resources from 24 Member States and Participating States, ready for deployment to a disaster zone at short notice. These resources can be rescue or medical teams, experts, specialised equipment or transportation. Whenever a disaster strikes and a request for assistance via the EU Civil Protection Mechanism is received, assistance is drawn from this Pool.

https://ec.europa.eu/echo/what/civil-protection/european-civil-protection-pool_en

rescEU

The overall objective of the EU Civil Protection Mechanism is to strengthen cooperation between the EU Member States and 6 Participating States in the field of civil protection, with a view to improve prevention, preparedness and response to disasters.

When the scale of an emergency overwhelms the response capabilities of a country, it can request assistance via the Mechanism.

Receiving support

The Host Nation Support Guidelines are most likely the most relevant reference for European countries receiving support in case of a major incident. However, for the sake of completeness and since topics might be of relevance for persons interested in the topic of international cross-organisational collaboration, also the link to the humanitarian sector and the UNDAC Field handbook and the OSOCC guidelines is established below.

EU Civil Protection: Host Nation Support Guidelines

The EU Host Nation Support Guidelines (EU HNSG) aim at assisting the affected

Participating States to receive international assistance in the most effective and efficient manner.

It encompasses supporting checklists and templates. These cover topics such as

-Emergency Planning

-Logistics/Transport or

-Legal and Financial Issues

https://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/about/COMM_PDF_SWD 20120169_F_EN_.pdf

Humanitarian Aid: UNDAC Field and book

UNDAC has evolved and adapted to the changing requirements of the international humanitarian response system and today also provides valuable support in protracted crises, technological and other types of emergencies.

In this role, UNDAC ensures effective collaboration between national disaster management systems, international humanitarian response actors, bilateral responders including the military, national non-government organizations, civil society and the private sector.

The Field Handbook is intended as an easily accessible reference guide for members of an UNDAC team before and during a mission to a disaster or emergency, covering the following topics:

- The international emergency environment;

- The UNDAC Concept;

- Pre-mission;

- On-mission;

- Mission end;

- Team management;

- Safety and security;

- Information management planning;

- Assessment and analysis (A&A);

- Reporting and analytical outputs;

- Media;

- Coordination;

- OSOCC concept;

- Coordination cells;

- Regional approaches;

- Disaster logistics;

- ICT and technical equipment;

- Facilities; S. Personal health.

https://www.unocha.org/our-work/coordination/un-disaster-assessment-and-coordination-undac

OSOCC Guidelines

Developed by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the International Search and Rescue Advisory Group network (INSARAG),

the On-Site Operations Coordination Centre (OSOCC) is a rapid response tool that provides a platform for the coordination of international response activities in the immediate aftermath of a sudden-onset emergency or a rapid change in a complex emergency.

OSOCC refers at the same time to both the methodology and the physical location, where on-site emergency response is coordinated. It thus deploys two simultaneous strategies:

to rapidly provide a means to facilitate on-site cooperation, coordination and information management between international responders and the government of the affected country in the absence of an alternate coordination system.

to establish a physical space to act as a single point of service for incoming response teams, notably in the case of a sudden-onset disaster where the coordination of many international response teams is critical to ensure optimal rescue efforts.

INSARAG Guidelines Volume I: Policy

https://www.unocha.org/our-work/coordination/site-operations-coordination-centre-osocc

INTERNATIONAL GUIDELINES (THEMATIC ASPECTS)

Besides general aspects of international cross-organisational collaboration, thematic approaches have been taken to enhance collaboration. For example, in the field of Search and Rescue (SAR) or Foreign Medical Teams (FMT) advances have been made to enhance collaboration. Furthermore, a link to the MEND Guide for planning mass evacuations is made:

INSARAG Guidelines

The INSARAG Guidelines provide a methodology to guide countries affected by a sudden-onset disaster causing large-scale structural collapse, as well as international USAR teams responding in the affected country.

The INSARAG methodology provides a process for preparedness, cooperation and coordination of the national and international participants. The guidelines also outline the role of the UN in assisting affected countries in on-site coordination.

The INSARAG Guidelines define a range of standards, notably about the size and tasks of USAR response teams:

a) Light Teams with basic operational capability to assist with the surface search and rescue of victims in the immediate aftermath of a sudden-onset structural collapse disaster; not deployed internationally.

b) Medium Teams cover the core competencies of management, logistic, search, rescue and medical and are equipped to conduct complex technical search and rescue operations in medium-heavy collapsed or failed structures, as well as rigging and lifting operations covering one worksite.

c) Heavy Teams fulfil all requirements as above to conduct complex technical search and rescue operations particularly in collapsed or failed structures build with reinforced or structural steel. They are expected to have the capacity to work two worksites simultaneously and for assignments longer than 24hrs.

FMT Guidelines

Following sudden-onset disasters (SODs), a large number of Foreign Medical Teams (FMTs) often arrive in-country to provide emergency care to patients with traumatic injuries and other life-threatening conditions.

Experience has shown that in many cases the deployment of FMTs is not based on assessed needs and that there is wide variation in their capacities, competencies and adherence to professional ethics. Such teams are often unfamiliar with the international emergency response systems and standards, and may not integrate smoothly into the usual coordination mechanisms.

Following the Haiti earthquake and Pakistan floods of 2010, where the problem outlined above were especially evident, The Global Health Cluster of the World Health Organization published the Classification and Minimum Standards for Foreign Medical Teams in Sudden Onset Disasters (FMT Guide).

It outlines a classification system and minimum standards for FMTs that provide trauma and surgical care in the first month following a SOD. Additionally, the FMT Guide provides a registration form for arriving foreign medical teams to fill out that allows FMTs to declare their services and capacities, and an overview of the classification system, principles and standards teams should meet when offering their services to affected countries. The ambition of the guideline is to maintain an overview of actors and improve the coordination of the foreign medical team response. Personnel is expected to have sufficient training and experience, further training guidelines are not part of the FMT Guide.

https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/foreign-medical-teams/en/

MEND Guide (Mass evacuation)

The Guide for Planning Mass Evacuations in Natural Disasters (MEND Guide) was created 2014 at the request of several countries and national disaster management authorities to help in the creation of (e.g. national) mass evacuation plans.

While It focuses on mass evacuations in the context of disasters related to natural hazard events, many of the actions suggested in this guide may also be applicable to other types of disasters and to planning for the evacuation of smaller groups of people. It serves as a reference providing key background considerations and a template to assist planning bodies at national, regional, municipal, and other levels – both urban and rural – in the development and/or refinement of evacuation plans in accordance with emergency management principles.

Training and Exercises

At the EU/international level, examples for cross-organisational training and exercises are listed below:

Training and Exercise

EU (UCPM)

The EU Civil Protection Mechanism runs an active and comprehensive training programme, offering experts from all over Europe a deeper knowledge of the requirements of European civil protection missions. The training helps experts improve their coordination and assessment skills in disaster response.

The programme offers a wide range of courses from basic training to high-level sessions for future mission leaders. Special courses are also available aiming to prepare for specific aspects of missions such as security training or assessments.

In addition, the expert exchange system of the EU Civil Protection Mechanism allows for the secondment of civil protection experts from one EU Member State or Participating State to another. This exchange provides participants with knowledge and experience on all aspects of emergency intervention and the different approaches of national systems.

https://ec.europa.eu/echo/what/civil-protection/experts-training-and-exchange_en

DG ECHO (Directorate General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations) funds a number of exercises every year to improve preparedness and enhance collaboration among European civil protection authorities and teams.

Modules Field Exercises aim to provide an opportunity for testing specific response capacities, as well as the self-sufficiency, interoperability, coordination and procedures of response teams and equipment.

Modules Table-Top Exercises, focus on in-depth training of modules, Technical Assistance and Support Teams and EU Civil Protection Teams key personnel. Contingency planning, decision-making procedures, provision of information to the public and the media can also be tested during the exercises. Exercises help stakeholders identify further training needs for their staff, while lessons-learned workshops organised in parallel serve as a forum to identify how response and related activities can be improved.

Initiation of cross-organisational collaboration

A good starting point to further develop cross-organisational collaboration or interoperability should be developed. This can be done by reviewing past event. For example, in the UK, the Pollock report (2013) revealed lessons from more than 30 incidents (https://www.jesip.org.uk/uploads/media/pdf/Pollock_Review_Oct_2013.pdf).

Similarly, a review of the interoperability dimensions might be a good starting point. For example, Testelmans (2017) reviewed these dimensions for the Belgian context (2017, https://www.cidss.be/publications/interoperability-dutch)

In terms of practical aspects, cross-ministry activity is supportive to enhance cross-organisational collaboration.

Also in the international context, the continuum might be applied for assessments on a case-by-case basis. For example, it was applied to assess the interoperability of French UCPM modules in the Swedish system which were deployed in 2018 (Mannaioni et al. 2020).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

These are essential to highlight and better understand the differences that exist, build trust amongst diverse individuals, and solidarity. Working groups established alongside any new tool or protocol can greatly improve the familiarity necessary for transboundary users to know what differences exist, and build trust and solidarity. Those will not come from the tools alone, but in proactive (not reactive) relationships. These working groups also should not restrict membership be a top-down determination but let all possible groups involved determine if this is of interest to them (e.g. don’t let one agency’s definition of the problem define who works together). A health official might be able to see that a traffic problem will require bodily care while a police officer might just define it as a security issue.

Maintenance

Based on an interoperability matrix (see section above), different dimensions of collaboration can be developed continuously through the development of frameworks, training and exercises, the use of new technology and finally the integration of lessons learnt into the system. In the UK for example, a dedicated joint organisational learning platform was developed: https://www.jesip.org.uk/joint-organisation-learning. Lessons identified during debriefings and notable practices are registered in a joint database. They are reviewed and eventually – after further evaluation – integrated into the training programme.

While much of this is organisational in nature, there are ethical aspects to consider. To ensure continuous transparency and adherence to ethical practices within collaborations it is essential for technical measures to be paired with social and organisational practices that raise awareness and reflexivity (Powles and Nissembaum, 2018).

Powles, J. & Nissenbaum, H. (2018). The Seductive Diversion of ‘Solving’ Bias in Artificial Intelligence. Medium. https://medium.com/s/story/the-seductive-diversion-of-solving-bias-in-artificial-intelligence-890df5e5ef53